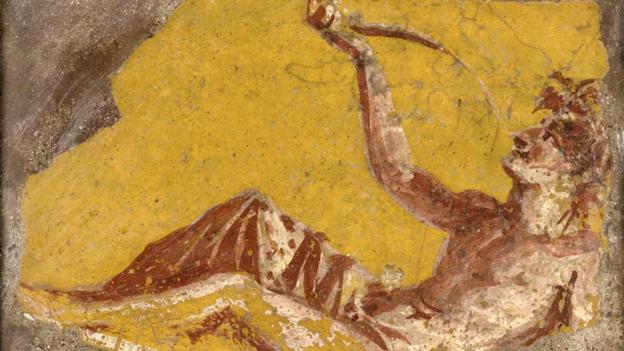

The Romans loved art full of violence and sex. But where modern viewers see smut and gore, ancient eyes may have seen something different, writes Alastair Sooke.

It must have been bliss to be an archaeologist during the 18th Century, when the Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum were rediscovered. Take the Villa of the Papyri outside Herculaneum: 85 sculptures were uncovered at this site alone between 1750 and 1761.

But it could be awkward too. Imagine how the excavators must have felt when they unearthed the most infamous of these sculptures in the presence of the king of Naples and Sicily on a spring day in 1752. Carved from a single block of Italian marble, it showed the wild god Pan making love to a goat. With his right hand, Pan grabs the nanny goat’s tufted beard, yanking forward her head so that he can stare deep into her eyes. The king was not amused.

Unlike most of the 18th-Century finds from Herculaneum and Pompeii, the sculpture was hidden away, available to view only with the monarch’s permission. Yet, from the moment of its discovery, the statue generated curiosity as well as horror. It quickly became a fashionable sight for Englishmen gallivanting around Europe on the Grand Tour. The 18th-Century English sculptor Joseph Nollekens produced a terracotta replica from memory – though his bug-eyed animal is far more surprised by Pan’s attentions than the Roman goat, which seems almost complicit.

Without realising, Nollekens had stressed the scene’s undertones of bestiality and rape – even though the original may have appeared much less violent to the Romans. Different cultures view the same things in different ways. Art that we consider shockingly erotic or violent was commonplace in the Roman world.

Now, the sculpture of Pan and the goat is setting pulses racing once again. On loan from the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, where it is usually shown in the ‘Secret Cabinet’ alongside other erotic material from the ancient Roman world, the statue features in the British Museum’s major exhibition Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum, currently on show in London. A discreet label forewarns visitors that the exhibition “contains sexually explicit material”.

Grim gardens

Today it is tempting to view the sculpture as a piece of vile erotica – but I’m not so sure. The Villa of the Papyri also contained a library full of hundreds of scrolls, suggesting that the man who owned the sculpture was sophisticated and well-read.

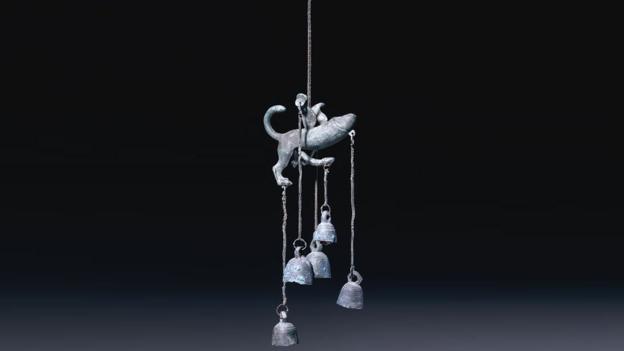

Perhaps he was also a provocative pervert who enjoyed scandalising his guests. But even a cursory acquaintance with the Roman world suggests that this wasn’t necessarily the case. Today some people decorate their gardens with gnomes. The Romans preferred sexier, gutsier, more bloodthirsty subjects. Elsewhere in the British Museum’s exhibition, we encounter two sublime marble sculptures depicting tense stags hollering with fear as they are overcome by snarling hunting dogs. The hounds gnash at the ears of their prey, using their claws to gouge deep into flesh.

These sculptures aren’t lewd, but they are extraordinarily violent. While we can appreciate the way in which the sculptor arranged a chaotic subject into coherent forms, they still seem like strange choices for garden ornaments, by our standards. So does a nearby marble statuette of a pot-bellied Hercules, clearly the worse for wear following a drunken banquet, about to take a pee.

But the Romans couldn’t get enough of this sort of stuff. One of my favourite Roman sculptures is the Hanging Marsyas. This presents the bearded satyr, Marsyas, bound to a tree. He is about to be flayed alive as punishment for challenging the lyre-playing god Apollo to a musical contest (inevitably, he lost). Several sculptures depicting this scene have survived, including a handful carved from purple-veined marble, which offers a grisly sense of the bloody flesh about to be revealed by the torturer’s knife.

It is a similar story with the famous Laocoon, that tangle of thrusting limbs, lightning-quick sea serpents and agonised expressions that has haunted the Western imagination ever since it was discovered in Rome and deposited in the Belvedere courtyard of the Vatican by Pope Julius II in 1506. This moving marble sculpture of the Trojan priest Laocoon and his two sons struggling to escape from the coils of their fate, forever frozen in the throes of anguish, has inspired countless artists and writers, from Michelangelo to Dickens.

It puzzles me that the Romans, who valued integrity and gravitas, were so obsessed with gore. After all, their gladiatorial games and spectacles in the arena involving wild beasts and condemned criminals were nothing but a form of ritualised human sacrifice. Ancient Rome was a curious mixture of civilisation and barbarism.

Saucy sculpture

China Yuan RMB

China Yuan RMB U.S. Dollar

U.S. Dollar Euro

Euro British Pound

British Pound Canadian Dollars

Canadian Dollars Australian Dollars

Australian Dollars Hong Kong Dollars

Hong Kong Dollars Vietnamese Dong

Vietnamese Dong More Info

More Info